Summary

Executive Summary

Excess profits taxes are taxes on profits above expected rates of return on investment. Excess profits can stem from monopoly power, wars, or other crises. They were implemented by Canada during both world wars and have been implemented in India, Nigeria, the United Kingdom and across Europe since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

From 2021 through 2023, Canadian corporations collected $441 billion more in profits than expected based on the average rate of return on assets over the previous decade. By definition, these are “excess” profits, and they contributed to the high levels of inflation experienced during this period. These profits could be taxed without affecting future investment decisions.

“From 2021 through 2023, Canadian corporations collected $441 billion more in profits than expected based on the average rate of return on assets over the previous decade. By definition, these are “excess” profits”

Canada has also experienced a decrease in competition over time, which is leading to large firms having an increased ability to raise prices without fear of losing market share. In addition to regulatory changes, the corporate income tax system could be redesigned to discourage mergers between large firms.

To raise funds urgently needed to address the climate and affordability crises and curb growing monopoly power, we recommend the implementation of an economy-wide windfall profits tax that could raise over $50 billion from publicly traded companies and a monopoly profits tax that could raise $8 billion annually.

Report

What is an excess profits tax?

An excess profits tax is a tax on profits that are larger than an expected “normal” rate of return on investment. Of course, expected “normal” returns on investment change over time in response to changes in policy, technology, the balance of power between workers and capitalists, and other market conditions. However, there are periods when it is clear that companies have collected excess profits. Excess profits can occur due to monopoly power, significant increases in public spending, unique events, or combinations of all of these. The term windfall profits is sometimes used more specifically to “refer to unanticipated, fortuitous gains typically generated by exceptional unexpected events such as wars, natural disasters, or pandemics”.

Excess profits taxes differ from typical corporate income taxes because they target what economists call “economic rents”. This indicates returns that are not needed to incentivize production and are collected on the basis of owning a particular asset or unique market conditions rather than for producing a good or service. Firms make investment decisions based on expected rates of return. Unexpected events that temporarily increase profits do not change future expected rates of return and so well-targeted excess profits taxes should not affect firms’ investment decisions. For this reason, excess profits taxes are supported by a wide range of economists across the political spectrum.

This report details recent and historical examples of excess profits taxes, explains why an excess profits tax is desirable in Canada now, and makes concrete recommendations for how it could be implemented.

Examples of excess profits taxes

Excess profits taxes in Canada

Canada has a long history of using excess profits taxes. During both world wars, excess profits taxes were implemented to help fund the war effort and to ensure that private companies did not profit during a time of national emergency. These were designed as taxes on profits above average profits in a specified pre-war period. During WWII, profits above this level were taxed at 75%, increasing to 100% with a 20% post-war tax credit in 1942. The general corporate income tax rate was also increased by 10 percentage points during WWII. These taxes were motivated by a popular idea that “no man should find himself richer at the end of this war than he was at the beginning.” An analysis of the 80 largest Canadian companies at the time showed that after-tax profits were virtually the same before and after the imposition of the excess profits tax, indicating that the tax was well-targeted at profits that derived directly from the war and did not lead to reductions in production.

“Canada has a long history of using excess profits taxes. During both world wars, excess profits taxes were implemented to help fund the war effort and to ensure that private companies did not profit during a time of national emergency.”

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, Canada again implemented an excess profits tax. Like the tax changes in WWII, this policy involved two prongs - a temporary tax on profits above a certain threshold and a permanent increase in the corporate income tax rate. Unlike those implemented in WWII, however, this policy was extremely limited in scope - the tax rates were much lower, and it was restricted to a single sector (large banks and life insurers). The Canada Recovery Dividend implemented a one-time 15% tax on the average of profits in 2020 and 2021 above $1 billion. The new permanent surtax on banks and life insurers increased the ongoing statutory corporate income tax rate by 1.5 percentage points on profits above $100 million. It should be noted that the Liberals’ original proposal was slightly more ambitious, but the policy was watered down after significant lobbying efforts. Despite the threats from industry, there is no evidence that these taxes have been passed on to consumers.

Excess profits taxes in other jurisdictions

Recognizing that corporations were able to accrue outsized profits during the COVID-19 pandemic, countries across the world have implemented excess profits taxes over the past several years. The European Union Council passed a Regulation in September 2022 that EU member states adopt windfall profits taxes on companies in the electricity and oil and gas sectors in the context of the extremely high energy prices that followed the Russian invasion of Ukraine. By August 2023, 20 EU countries had implemented their own versions of the windfall profits taxes proposed by the EU Regulation. International coordination on such taxes helps to ensure companies are not able to avoid them through shifting profits to lower tax jurisdictions. Although member states have leeway to adapt the form of the tax to their own context, most have followed the guidelines outlined by the EU Council. There are two main components of this tax.

First, it imposes a tax of at least 33% on profits that are above 120% of the average taxable profits from 2018 through 2021 for companies in the oil and gas sector. Many countries, including Austria, Italy, and Ireland, have imposed much higher tax rates than the minimum 33%. Some countries have extended this tax to other sectors that enjoyed excess profits during the pandemic, such as the banking sector and food retailers.

Second, the Council Regulation imposes a minimum 90% tax on revenue exceeding €180 per megawatt hour of electricity generated for electricity producers and intermediaries. Again, some countries have implemented even stricter revenue thresholds. The periods covered by these two taxes vary across countries, but most cover at least a portion of 2022 and 2023.

The United Kingdom, although no longer a part of the EU, has also implemented its own version of an excess profits tax on the oil and gas sector in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Its excess profits tax is not scheduled to be phased out until 2029 (or when oil prices fall below a certain level). The UK tax is modelled differently than the EU version - it imposes a surtax on all oil and gas profits, not only those profits above their previous average level (initially, it was set at 25%, but it has been raised to 38% as of fall 2024). However, this is offset by significant new investment tax credits. Overall, the policy means that oil and gas companies will receive a greater tax break than previously if they reinvest their profits but will pay more taxes than previously if they pay out their profits as dividends.

Outside Europe, in 2024, Nigeria implemented a 50% tax on bank profits from foreign exchange transactions collected in 2023. From 2022 through fall 2024, India implemented a tax on the production of crude oil that varied with fluctuations in oil prices.

Even the United States has historically made use of excess profits taxes. During both World War I and World War II, the US imposed excess profits taxes with rates as high as 95% on profits above a specified rate of return. In the 1980s, the US imposed a version of an excess profits tax on domestic oil production in response to the OPEC oil price shock and oil price decontrol. Similar to the EU tax on revenue above a certain price of electricity, this tax was structured as a tax on revenue above a certain oil price.

Progressive American lawmakers have also proposed an excess profits tax on large US companies after the pandemic. The proposed Ending Corporate Greed Act would impose a 95% tax on profits above their average level from 2015-2019 (adjusted for inflation).

The Canadian context - why urgent action is needed

From 2021 through 2023, Canadian companies collected record levels of profits. This had very little to do with increased production or new innovations. Instead, firms raised prices (or, in the case of firms selling to global commodity markets, benefitted from higher market prices) to increase their profit margins, contributing to inflation. While inflation and profits have since returned to normal levels, those earnings collected by large corporations have not been returned.

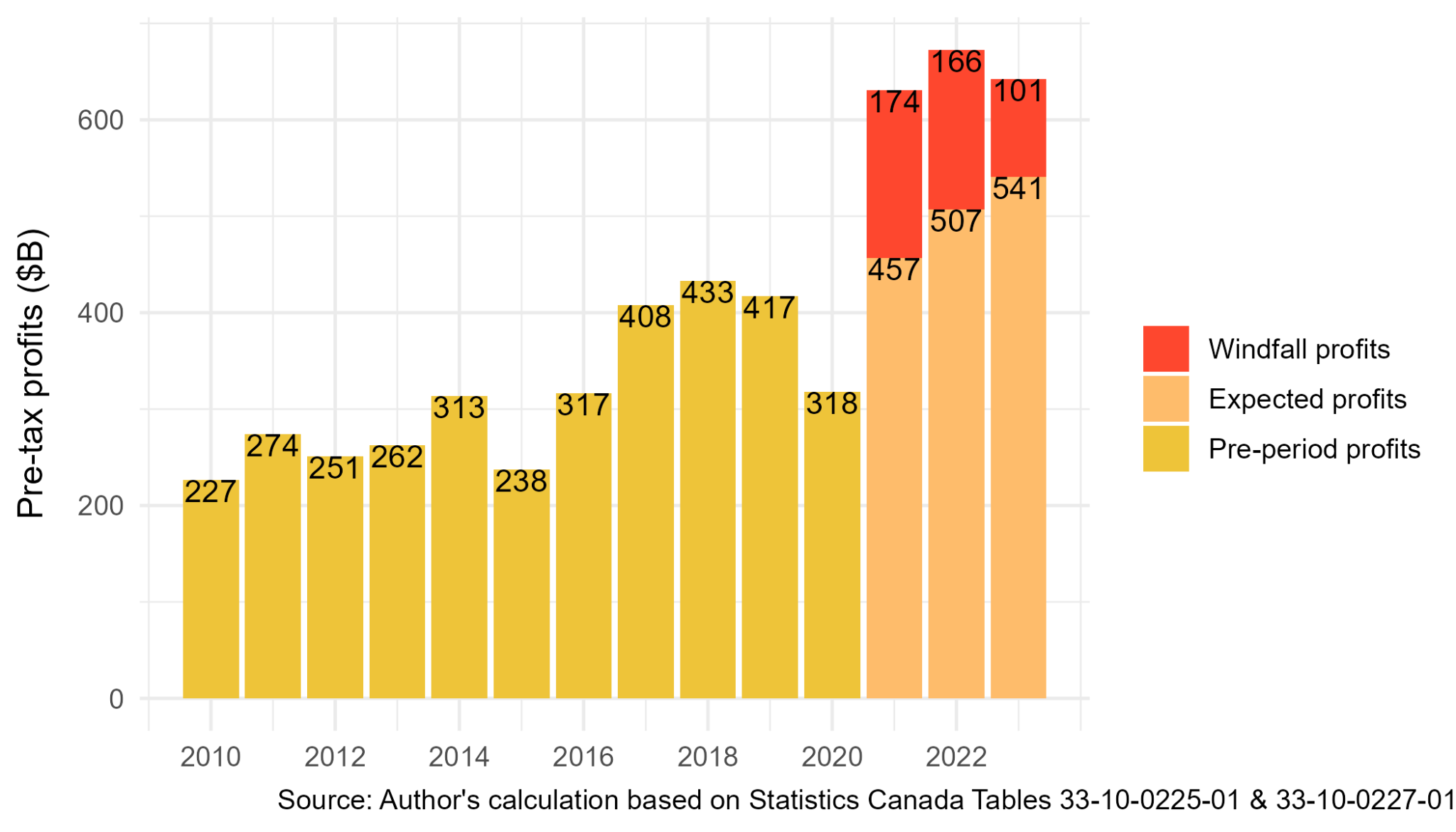

Figure 2 shows one way of estimating windfall profits during this period at the aggregate level. Windfall profits are estimated as the profits above those that would have been earned had the profit margin stayed at its average level over the 2017-2020 period. In 2021 and 2022, windfall profits were over $165 billion, at least 25% of corporate profits. Windfall profits fell slightly to $101 billion in 2023, but profits remained well above expected levels. These windfall profits could be taxed with a one-time retroactive tax, and firms would still be left with significant profits, ensuring continued incentive to invest.

A chart showing pre-tax profits from 2010 to 2022. Expected profits are calculated as the average profit margin from 2017 to 2020 times the total revenue in each year. Windfall profits are the difference between actual pre-tax profits and expected profits.

Figure 2. Estimates of total windfall profits, 2021-2023.

Note. Expected profits are calculated as the average profit margin from 2017 to 2020 times the total revenue in each year. Windfall profits are the difference between actual pre-tax profits and expected profits.

Market power and excess profits

A windfall profits tax on profits from 2021 to 2023, however, would not collect other forms of excess profits that arise from market power or other factors in the future. Outside of periods of crisis, it is very difficult to separate “normal” profits from “excess” profits. However, we do know that large multinational firms typically have a significant level of market power. Furthermore, this market power has been increasing over time. The Competition Bureau found that fewer firms are entering industries over time, the largest firms are facing less competition, and profit margins are increasing. These findings suggest that large firms are earning more and more excess profits.

This reduction in competition is likely one of the reasons that firms were able to collect such large windfall profits during the pandemic. The Competition Bureau’s grocery report said, “The fact that Canada's largest grocers have generally been able to increase these margins—however modestly—is a sign that there is room for more competition in Canada’s grocery industry”.

Taxes alone cannot solve the problem of rising market power, allowing large firms to set higher prices. The recent reforms to the Competition Act are a step in the right direction and must be backed up with strong enforcement. However, the tax system can also be designed to discourage concentration.

As Professor Reuven Avi-Yonah notes, the American corporate income tax system was originally designed to curb corporate concentration. For over 70 years, the corporate income tax system in the US, like the personal income tax system, was progressive - higher levels of taxable income faced higher tax rates. In Canada, we already have a form of progressive corporate income taxation - small businesses pay a lower tax rate than medium and large businesses. Since very large firms tend to have significant monopoly power, Avi-Yonah and the Washington Center for Equitable Growth recommend implementing a higher tax rate on taxable corporate income above a high threshold. This would target excess profits and discourage corporate consolidation.

Recommendations

We recommend that Canada implement a two-pronged excess profits tax to efficiently raise revenue to fund a just transition and build affordable housing while improving tax fairness and discouraging corporate consolidation. First, we recommend the implementation of a one-time 33% windfall profits tax on corporate profits collected in 2021, 2022, and 2023 above 120% of average profits from 2016 through 2020 for all firms with at least $10 million in profits. These taxable years are chosen because they followed the COVID-19 pandemic and levels of inflation were elevated during these years, in part due to excess profits. To address liquidity constraints, the tax could be payable over 5 years, like the Canada Recovery Dividend.

This tax should also remain on the books permanently, with a mechanism allowing it to be triggered during future crises. This would disincentivize firms from taking advantage of future crises to raise prices on essential goods, ensuring that, like during WWII, no corporation should be richer at the end of a crisis than at the beginning.

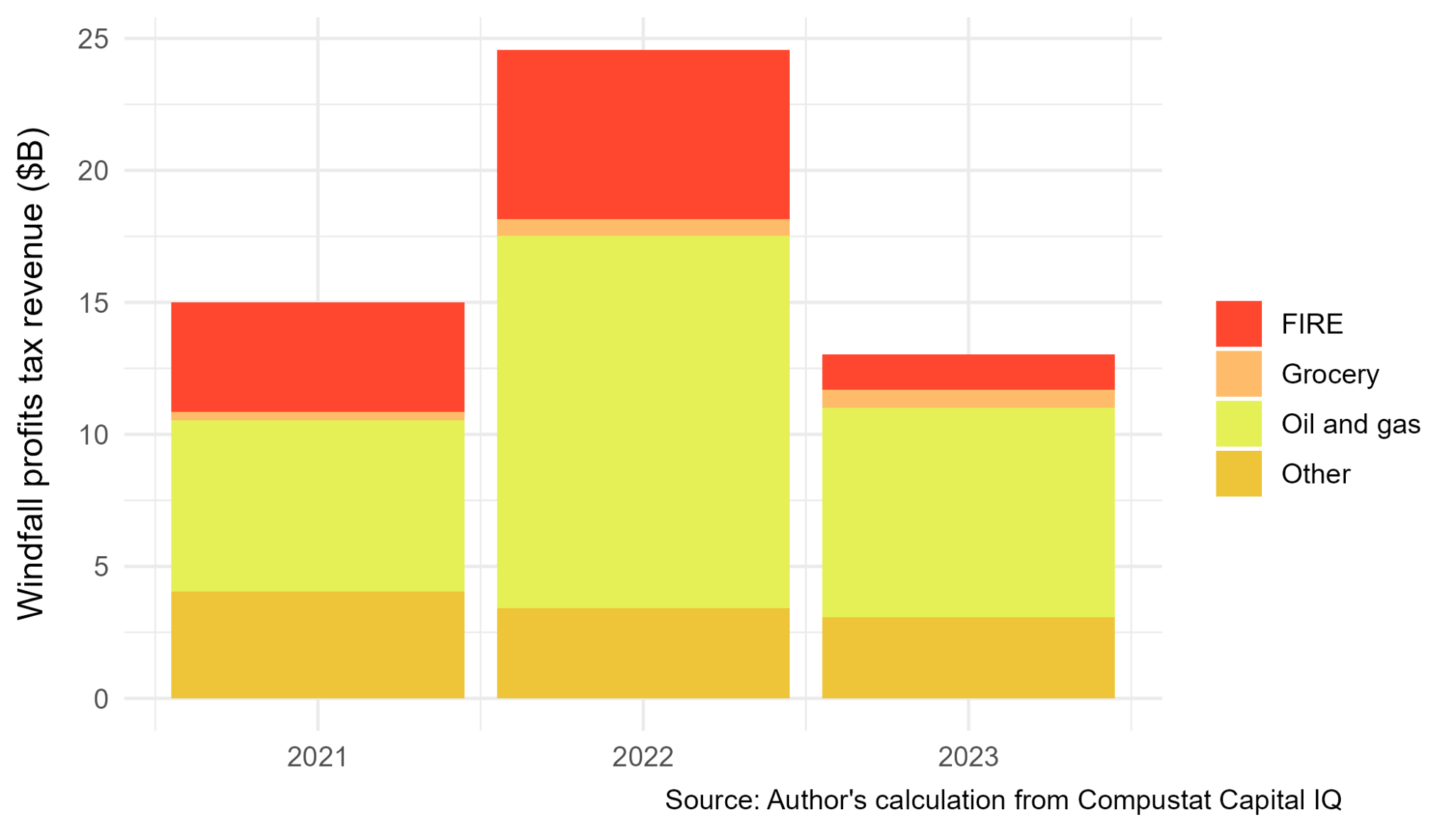

Using data for publicly listed companies, Figure 3 shows which sectors would be liable for the most tax under this policy. Unsurprisingly, over half (54%) of tax revenues would be raised from the oil and gas sector, and over 20% would come from the finance, insurance, and real estate sectors. However, an economy-wide tax would ensure that all firms were treated in the same way and discourage price-gouging in all sectors during future crises. We estimate that such a one-time tax could raise over $50 billion from publicly listed companies.

A bar chart showing windfall profits tax revenue for FIRE, grocery, oil & gas, and "other" sectors, for years 2021 to 2023.

Figure 3. Potential windfall profits tax revenue by sector and tax year.

Note. Firms with zero profits in the pre-period are allowed a 5% return on capital during the taxable years. “Oil and gas” includes companies primarily engaged in oil and gas extraction, refining, and transportation through pipelines. “FIRE” indicates firms in the finance, insurance, and real estate sectors.

Second, for tax years from 2024 onwards, we recommend a super-profits tax, a 5% increase to the corporate income tax rate for profits above $100 million on a consolidated basis (143 publicly traded companies met this threshold in 2023). This would impose a higher marginal tax rate on the profits of very large corporations that earn excess profits through their monopoly power. It follows a similar structure as the 1.5% surtax on banks and life insurance groups that was implemented in 2022 but applies to all sectors equally. We estimate that this policy could raise over $8 billion annually.

About Canadians for Tax Fairness

Canadians for Tax Fairness is a non-profit, non-partisan organization that advocates for fair and progressive tax policies, aimed at building a strong and sustainable economy, reducing inequalities, and funding quality public services.

About Silas Xuereb

Silas Xuereb is a researcher with years of experience in academia and working with non-profit organizations. He's passionate about conducting rigorous research to understand social and economic inequalities in support of actors working to alleviate them. He holds Master’s in Economics from UBC and the Paris School of Economics and is currently a PhD student at UMass Amherst.