Summary

Canada’s rental housing affordability crisis continues to worsen - in 2023, rents increased by 8% while wages grew only 5%. At the same time, the real estate sector collected $50.4 billion in profits in 2023, 40% higher than its pre-pandemic record. The increasing financialization of housing has contributed to the affordability crisis, and is exacerbated by preferential tax treatment for capital gains and real estate investment trusts (REITs).

As financialization of housing continues to spread across Canada, finance, insurance and real estate (FIRE) corporations are increasingly profiting off of the sale of financial and real estate assets, resulting in a 700% increase in real corporate capital gains since 2002. FIRE’s portion of corporate capital gains has increased over time, reaching 66% of the $86.9B in capital gains collected by corporations in 2022. Capital gains have increased from 1.2% of revenue in the FIRE sector in 2002 to 7.7% in 2022. The changes to the capital gains inclusion rate proposed by the federal government are critical to counteract the trend toward financialization of housing by bringing tax rates on capital gains closer to tax rates on other streams of income. Without it, billions in capital gains flow into corporate and investor bank accounts tax free.

The preferential taxation of REITs is another policy that encourages the financialization of housing and contributes to the housing affordability crisis. REITs, whose primary goal is to increase distributions to investors, now own over 200,000 residential rental units in Canada. Because rental income is factored into real estate property values, preferential capital gains taxation also increases the incentive for financialized landlords, such as REITs, to increase rents. Major residential REITs enthusiastically tell their investors that they raise rents more than inflation and market averages. In 2022, $100 million collected by the largest seven residential REITs was distributed to investors tax free through the partial inclusion of capital gains.

Stable, affordable housing is essential for a flourishing and equitable society. By converting housing into an investment asset, the increasing financialization of housing reduces both housing stability and affordability. The government must ensure that tax policy does not encourage this process. Instead, the government should focus on building housing and supporting non-market and cooperatively-owned housing.

Report

Introduction

Financialization refers to the increasing share of profits made through financial means. This includes profits made through credit and the ownership of assets rather than through producing goods and services.1 From 2002 to 2022, the share of total profits collected by the finance, insurance, and real estate (FIRE) sectors, sectors which earn the vast majority of their profits through financial means, increased from 29.6% to 35.3%.2 With regards to housing in particular, financialization indicates the increasing ownership of housing by financial actors (e.g., real estate investment trusts [REITs], private equity funds, and institutional investors) who use housing primarily as a financial asset to generate returns for third-party investors (although individual owners and small private corporations also aim to profit off of housing, they do not face the same competitive pressures as financial actors).

In this report, we show the impact of financialization on rental affordability and how government policy encourages financialization through tax breaks for capital gains and REITs. First, we document the rise in corporate capital gains and how this trend reflects growing financialization. Then, we examine how REITs use capital gains to reduce their tax burden while raising rents, threatening affordability, and posting massive profits. Finally, we discuss principles of taxation and recommend policy changes to curb the financialization of housing.

Financialization and corporate capital gains

As financial markets have expanded, corporations have had increasing opportunities to sell shares, real estate property, and other assets for financial gain. The average holding period for stocks is now less than one year, down from five years in the 1970s.3 Importantly, unlike other types of transactions undertaken by corporations, sales of financial assets do not create real economic value. This means they do not result in the production of a good or service that is consumed to meet someone’s wants or needs. For example, a company that pays a worker to bake a loaf of bread that is later sold produces real economic value. The sale of assets that result in a capital gain does not involve the production of goods or services. They simply transfer ownership of an asset from one party to another. Because of this, they are excluded from measures like Gross Domestic Product which purport to measure the magnitude of economic activity.4

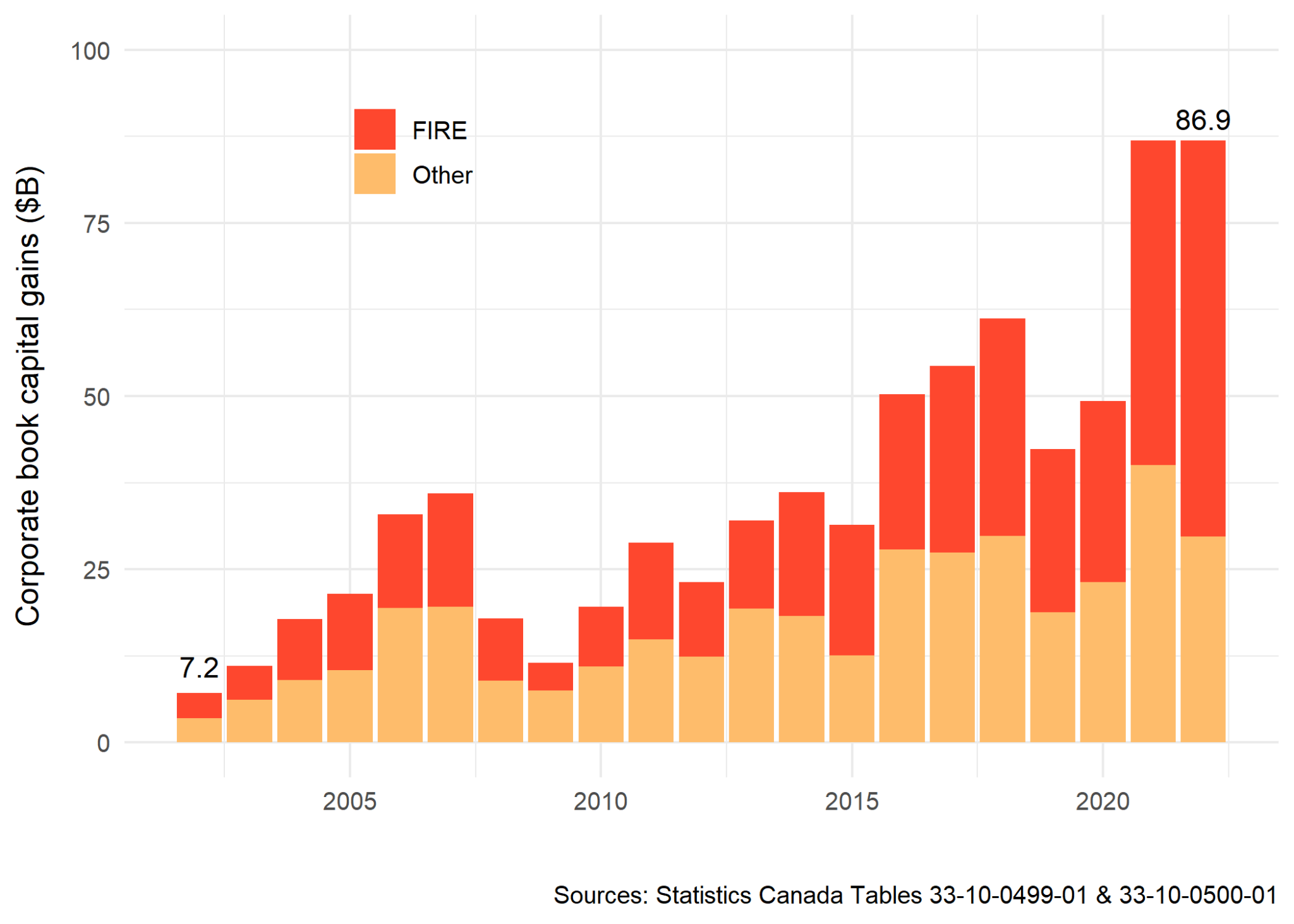

Figure 1 shows that corporate capital gains5 have increased by over 1100% from $7.2B in 2002 to $86.9B in 2022 (in CPI-adjusted dollars, the increase is over 700%).6

The rise in capital gains was especially steep in the FIRE sector, where $57.2B in capital gains were booked in 2022 (66% of all corporate capital gains) compared to just $3.7B 20 years earlier (51% of all corporate capital gains). Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the FIRE sector had never booked more than $31.4B in capital gains in a single year.

Figure 1. Corporate capital gains, 2002-2022. Note: FIRE - Finance, insurance and real estate (NAICS codes 52 and 531).

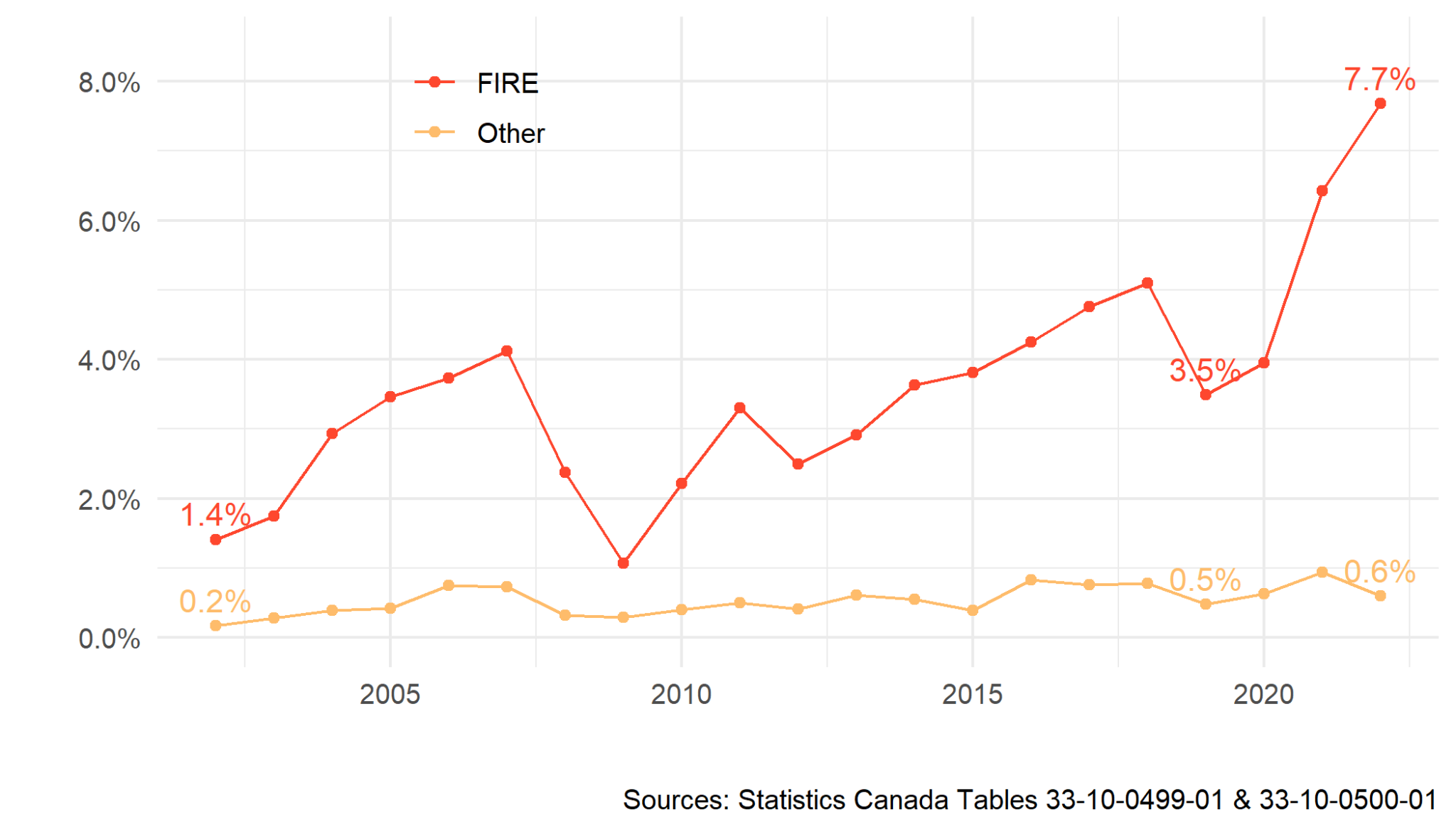

Not only have corporate capital gains been increasing overall, but they represent an increasing share of corporate revenue for companies in the FIRE sector (see Figure 2). In 2002, capital gains were 1.4% of total revenue in the FIRE sector and 0.2% of total revenue for all other corporations. Over the next five years, capital gains increased as a share of revenue for the FIRE sector, before falling during the financial crisis when many financial assets lost value. Since 2009, however, this ratio has steadily increased for the FIRE sector, reaching a record 7.7% in 2022. In non-financial sectors, this ratio has only slightly increased to 0.6% in 2022.

The rise of capital gains in the FIRE sector reflects the growing role of financial firms in owning and managing other companies and real estate. Importantly, it does not reflect an increase in real productive activity. It is also possible that financial firms are increasingly shifting their income to capital gains in order to take advantage of the preferential tax treatment afforded to this form of income, especially after the Chrétien government lowered the taxable portion of capital gains from 75% to 50% in 2000.

Figure 2. Ratio of corporate capital gains to total revenue by sector, 2002-2022.

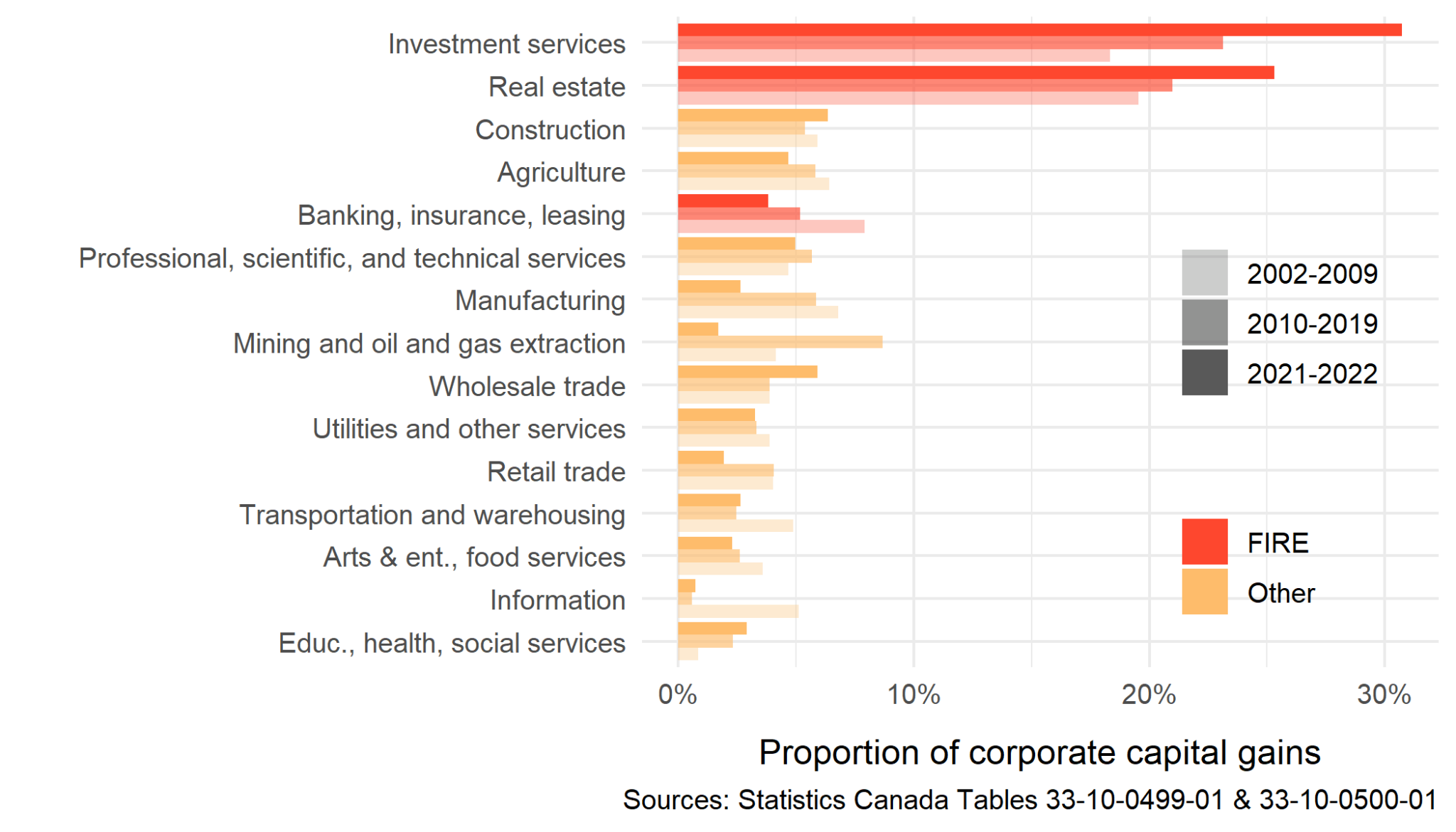

We can also break down corporate capital gains by industry at a more granular level. Figure 3 shows the proportion of corporate capital gains collected by each industry in three periods - 2002-2009, 2010-2019, and 2021-2022. Two industries within the FIRE sector stand out throughout all three periods - investment services7 and real estate. The investment services industry realized $26.7B in capital gains on average in 2021 and 2022 (30.7% of all corporate capital gains) compared to average annual capital gains of $8.8B in the 2010s (23.1%). Similarly, after realizing an average of $8.0B in capital gains per year throughout the 2010s (21.0%), the real estate industry recorded $22.0B on average in 2021 and 2022 (25.3%). The recent growth can be partially attributed to the rising property values of the pandemic but also reflects a longer-term trend of rising financial ownership of companies and real estate, which has been incentivized by the partial inclusion of capital gains.

Figure 3. Proportion of corporate capital gains by industry and period. Note. Investment services refers to NAICS code 523. Banking, insurance and leasing refers to NAICS codes 522, 524, 532, and 533. Utilities and other services include NAICS codes 22, 56, and 81. Other categories correspond directly to 2 or 3-digit NAICS categories.

To understand where the real estate sector earns capital gains, we have examined annual reports of publicly traded real estate investment trusts (REITs). Within the real estate industry, REITs have grown to two-thirds of real estate assets traded on the TSX.8 REITs are trusts that must hold the majority of their assets in real estate and distribute most of their profits to investors9 each year. Unlike corporations, which are subject to the corporate income tax, income is distributed to REIT investors without being taxed and then taxed at the individual level. According to the Parliamentary Budget Office, this tax exemption saves non-resident investors and those who hold their investments in tax-free accounts over $50 million per year.10 REITs can combine this exemption with the reduced capital gains inclusion rate to ensure investors pay very little tax, even when the majority of REITs’ income comes from rents paid by tenants.

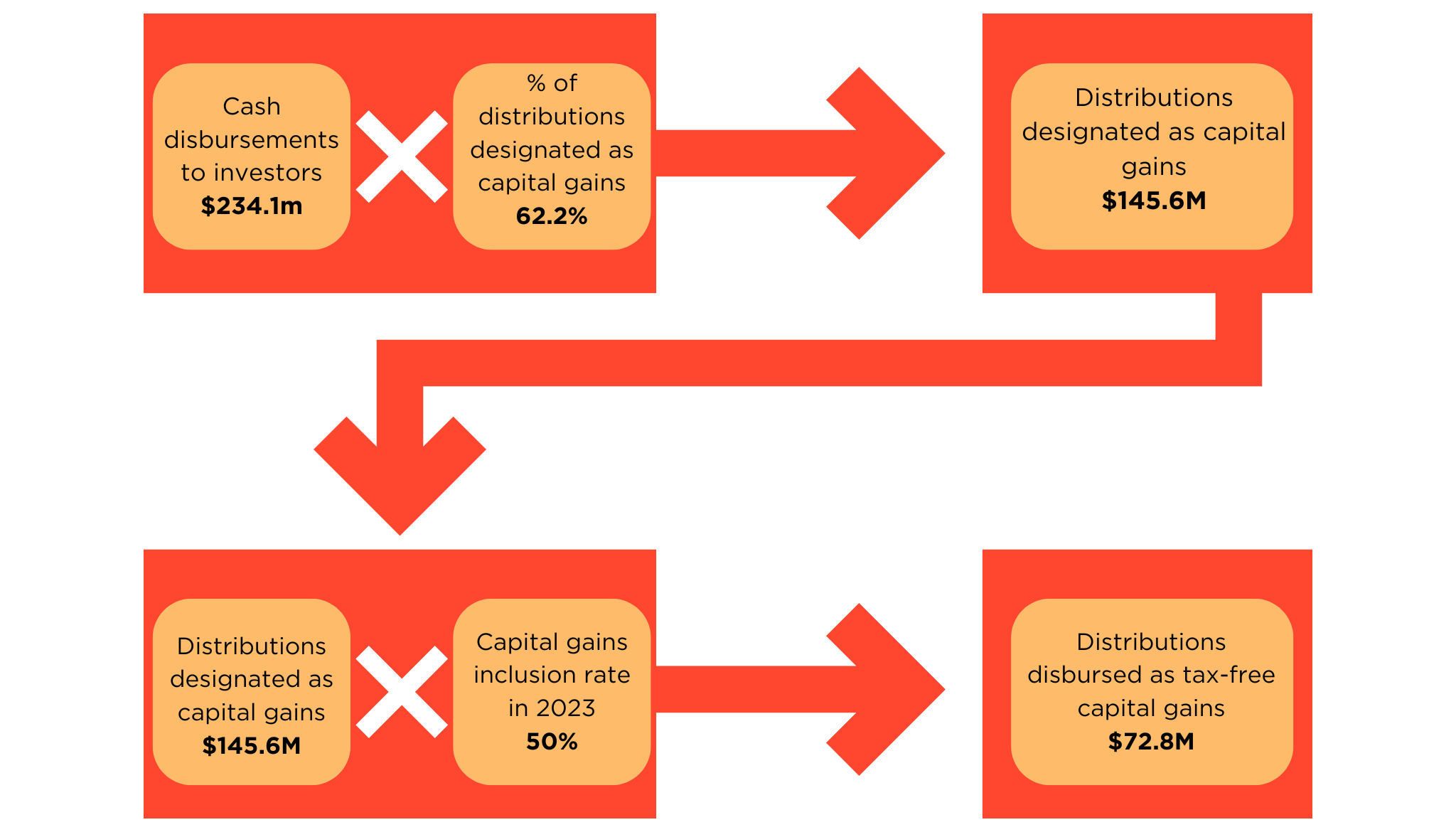

For example, in 2023, Canadian Apartment Properties (CAP) REIT, the largest Canadian residential REIT which owns over 45,000 residential units in Canada, sold 22 properties for over $424 million according to its annual report. These sales resulted in capital gains which allowed CAP REIT to distribute approximately $72.8 million to investors completely tax-free - because of the exclusion of 50% of capital gains from taxation, this money was not taxed at the level of the trust nor at the individual level.11 If REIT investments were held in tax-sheltered accounts, like Tax-Free Savings Accounts, then even more distributions may not have been subject to tax.

Figure 4. Calculation of tax-free distributions of capital gains for CAP REIT in 2023.

Financialization of housing and the housing affordability crisis

As capital gains have grown in the real estate sector, the sector has become more financialized, and a rental affordability crisis has emerged. Residential REITs, like CAP REIT, have gone from owning 0 rental units in 1996 to around 200,000 units today.12 More broadly, financial firms own 20-30% of purpose-built rental housing stock in Canada today and they are now the majority purchasers of multi-family dwellings.13 Across Canadian provinces for which data is available, 24-35% of residential properties, including single-family homes, were owned by people who do not live on the property in 2021.14 Homeownership rates declined over the last decade after rising consistently from 1971 to 2011.15

What does this have to do with capital gains and rental affordability? Financial firms, such as REITs, hold properties “for the purpose of producing rental income, capital appreciation or both”.16 Importantly, these two goals - rental income and capital appreciation - are intimately related. The value of financial assets - and rental properties are treated as financial assets by financial firms - is often determined by dividing the financial flows that the asset produces annually by a “capitalization rate”.17 According to REITs and their auditors, the value of their real estate assets is a direct function of the properties’ rental income.18 Boardwalk REIT’s 2023 annual report shows that the fair value of its investment properties increased by $599 million in 2023, in large part because it increased rents at its properties by 8.8% on average while its rental expenses increased by only 1.6%.19

By increasing rents, financial firms increase both their flow of rental income and the value of their investment properties, resulting in a larger capital gain when sold. The partial inclusion of capital gains and the tax exemption for REITs thus both incentivize increasing rents for Canadians. Given existing rent control laws in many provinces which cap rent increases only on occupied apartments, these exemptions also increase firms’ incentives to evict tenants so that they can increase rents without restriction. If these tax exemptions did not exist, it would be less profitable to evict tenants and increase rents.

Financialized firms, including REITs, are market leaders in raising rents and evicting tenants.20 In its 2023 annual report, Centurion Apartment REIT enthused, "The REIT has grown its Same Store NOI, Total Operating Revenues and Market rents significantly faster than market averages and inflation benchmarks". That year, Centurion increased their same property average rent by 7.6%.21

According to CMHC, average rents increased far faster in 2023 for apartments (8.0%), which are more likely to be owned by financial firms,22 than for condos (6.0%).23 However, financial firms are starting to move into purchasing condos and single-family homes,24 so the current trends in apartments may soon be evident in other forms of rental housing as well.

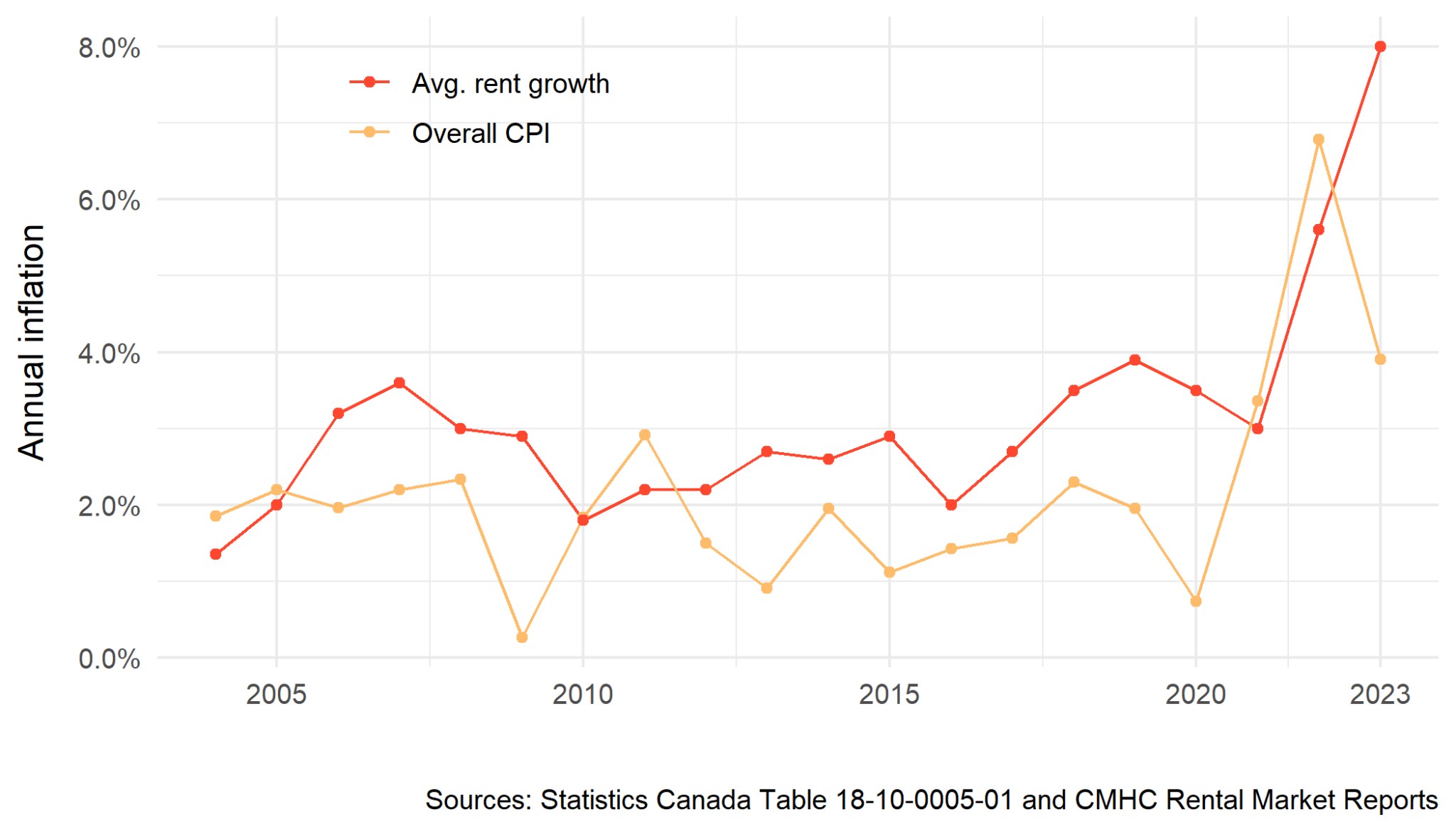

Since the pandemic, these trends have manifested in a rental affordability crisis. Figure 5 displays overall annual inflation and average rent increases from 2004 through 2023. Rent increases reached record levels in 2022 (5.6%) and 2023 (8.0%), far outpacing overall inflation (3.4%) and wage growth (5%)25 in 2023. In many provinces, rent increases are capped by rent controls for units where the tenant does not move. For units where the tenant moved out, the average rent increase reached a staggering 18.3% in 2022 and 23.8% in 2023.23

Figure 5. Overall Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation and rent inflation, 2004-2023.

Tax avoidance through residential REITs

The financialization of housing (and real estate more generally) has been encouraged by government policies, including the partial inclusion of capital gains and the REIT exemption. In this section, we show how these loopholes reduce investors’ tax burden and incentivize investment in REITs.

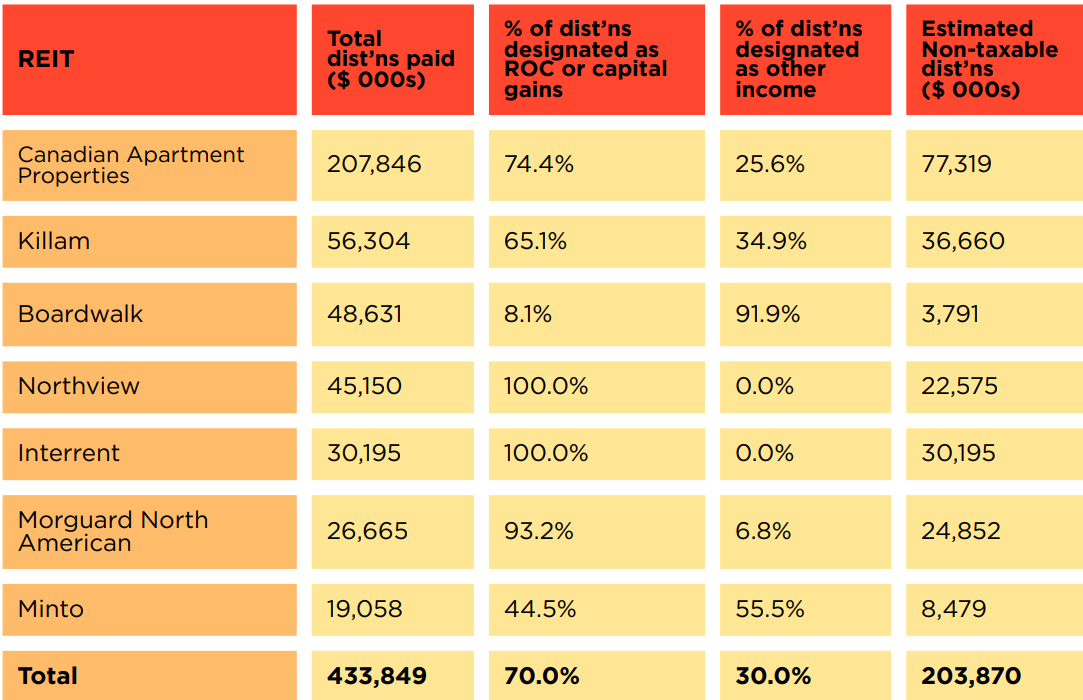

Distributions to investors from REITs can be designated as different forms of income, including regular investment income, dividends, capital gains, and returns of capital (ROC).26 Table 1 shows the proportion of distributions to investors designated as capital gains and ROC for the 7 largest publicly traded residential REITs in Canada in 2022.27 REITs take advantage of the preferential tax treatment of capital gains and ROC to reduce their tax burden. Even though most REIT income comes from rents (for example, CAP REIT collected over $1 billion in operating revenue in 2022 but less than $400 million in cash from property sales), REITs are able to designate most of their distributions as capital gains or ROC.

Table 1. Distributions to investors as capital gains and returns of capital (ROC) by seven largest residential REITs, 2022. Sources: Canadians for Tax Fairness calculations based on data from publicly available annual reports and company websites. Note. Non-taxable distributions in this table refer to distributions that are not taxable while the investor still holds the unit. It is calculated as 50% of capital gains plus 100% of returns of capital. A higher tax bill will be incurred upon the sale of the unit in response to distributions designated as returns of capital.

We focus on residential REITs because of their direct relation to the housing affordability crisis. Combined, these 7 REITs, which owned over 158,000 residential units in 2022, paid out over $433 million to their unitholders. By designating much of this income as capital gains and returns on capital, over $203 million, or 47% of distributions, was not taxable at the time of distribution, neither at the level of the trust nor at the level of the individual. Further distributions may have been non-taxable if they were held in tax-sheltered accounts.

To be clear, all this tax avoidance is perfectly legal. But it demonstrates the way that tax loopholes have been combined by wealthy shareholders who are profiting off of tenants who need a place to live. Given the rise of capital gains in the real estate sector over time, it appears that these forms of tax avoidance are becoming more common as the financialization of housing progresses.

Profits in the real estate industry

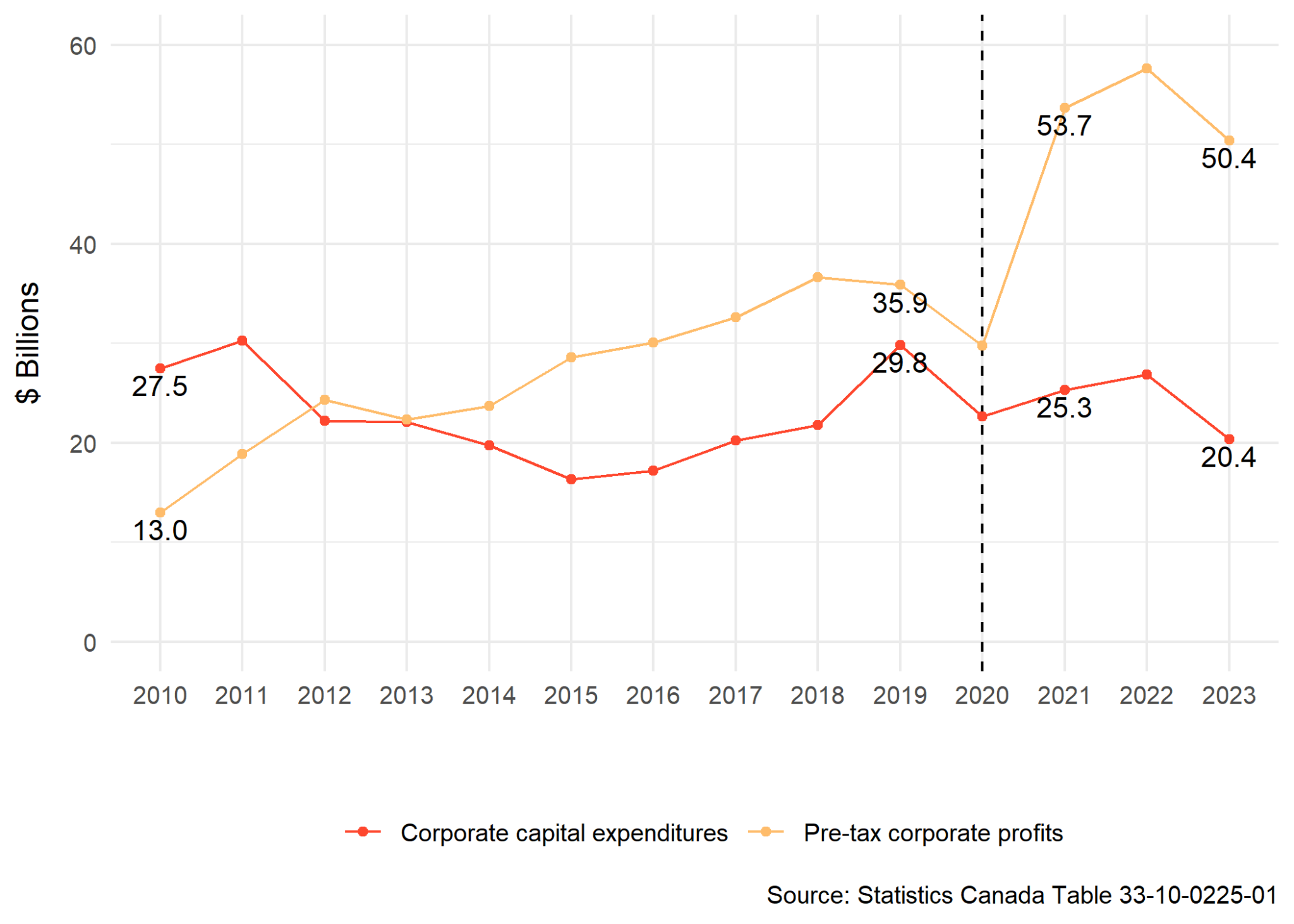

While taking advantage of tax loopholes and raising rents to record levels, profits in the real estate industry reached unprecedented heights during the pandemic. Figure 6 displays pre-tax corporate profits in the real estate industry from 2010 to 2023. The real estate industry includes firms that own, manage and lease residential and non-residential real estate, as well as real estate agents, brokers, and appraisers.28 Profits have been rising in the real estate industry since well before the pandemic. This reflects not only the general rise in real estate prices over time but also the increasing ownership of real estate by corporations, trusts, and individuals who treat real estate as a financial asset as opposed to a place to live. However, since the COVID-19 pandemic, corporate profits skyrocketed in the real estate industry, while investment remained stagnant, as it did in many other industries.29 Record profits in the real estate industry, which largely stem from rents, are not being reinvested.

Figure 6. Pre-tax corporate profits and capital expenditures in the real estate industry, 2010-2023.

Rising housing demand during a period of ultra-low interest rates certainly played a role in increasing housing prices early in the pandemic, contributing to rising profits in the real estate industry. However, real estate lessors, especially financial firms, also chose to increase rents. Boardwalk REIT’s 2023 annual report says they “continue to self-moderate the pace of rental adjustments on both new leases and lease renewals in our non-price controlled markets” in order to “balance” residents’ experience and sustainable returns.30 During 2023, Boardwalk REIT increased their same property average rent by 8.8%.

Why are landlords able to increase rents so drastically when they choose to? What does this imply for policy solutions?

Price-setting and incentives: considerations for capital gains and the rental market

Market power and price-setting in the rental market

Neoclassical economic theory, upon which most of our policy framework has been established, assumes that prices are determined in competitive markets where no buyer or seller has power over another. This constrains sellers’ ability to increase prices because buyers will simply choose not to buy a product for which the price is too high (demand will fall when prices are raised).

However, this is not how markets for essential goods like housing work. Renters cannot choose not to rent an apartment (unless they have the capital to purchase a home, something which is increasingly unlikely for younger generations). This creates a power imbalance in the market: needing a place to live, renters are forced to pay whatever price is asked, while financial landlords can easily find other tenants. For incumbent tenants faced with rent increases, the imbalance is even larger - to move would involve uprooting one’s life and giving up one’s community. Instead of being constrained by perfect competition, landlords’ rent increases are constrained by expectations and tenants’ ability to pay. As described by Boardwalk REIT, prices are set to ensure residents’ perception of Boardwalk remains positive and to ensure that rent adjustments are “sustainable” (i.e., that residents can afford them).31

Landlords were able to take advantage of their price-setting power to raise rents significantly during the pandemic and the accompanying inflationary period. This phenomenon is known as sellers’ inflation.32 This is especially concerning given that changes in housing prices have an outsized impact on overall inflation (and thus the purchasing power of workers) because it is essential.33 Workers cannot simply choose to stop buying housing for a month. Because of the financial logic that guides financialized landlords, sellers’ inflation is more likely in concentrated markets full of financial landlords as opposed to one composed of smaller landlords who primarily view themselves as housing providers.

Taxation principles

In this section, we’ll discuss conventional economic principles of taxation and why they provide no justification for tax exemptions for capital gains and REITs. Economists generally have broad consensus on a few principles of taxation that should be followed regardless of the chosen level of taxation. The Mirrlees Tax Review, commissioned by the UK government and undertaken by prestigious economists from around the world in 2011, summarizes these principles as 1) neutrality, 2) simplicity, and 3) stability.

The principle of neutrality is the idea that different forms of income should be taxed at the same rate. According to the Mirrlees Review, “In a non-neutral tax system, people and firms have an incentive to devote socially wasteful effort to reducing their tax payments by changing the form or substance of their activities”. The preferential treatment of capital gains income is a quintessential example of non-neutrality: it incentivizes actors to convert other types of income into capital gains.

Non-neutrality may be desirable when taxes are used to (dis)incentivize a particular behavior - but there is no clear reason why we want to encourage the sale of assets rather than investment in the production of goods and services. There is no evidence that preferential capital gains taxation increases growth.34 By taxing capital gains at a lower rate than other forms of income, we encourage investors to purchase financial assets that are expected to rise in value, rather than investing in new productive equipment that could increase real economic activity.

A simple tax system means there should not be too many exceptions or complications in the tax system. These exceptions give rise to tax avoidance and contribute to the tax gap - the difference between the statutory tax rate and actual taxes paid. A stable tax system is predictable and built on a set of clear principles. Our tax system should be fair and treat different forms of income the same way.

Another important component of the economic theory of taxation is that economic rents can be taxed without affecting economic decisions. An economic rent is not the same as the rent paid to lease an apartment. Economic rents are payments that are made simply for owning assets rather than to ensure a good or service is produced. The best example is returns on land ownership - because there is a fixed quantity of land that will exist regardless of the payment received by its owners, returns to land are generally considered pure economic rents. This has been acknowledged by economists for hundreds of years,35 and was reconfirmed by the Mirrlees review.36

A significant portion of capital gains, especially those accruing to the real estate industry, are economic rents that stem from increases in land values. Land value appreciation is typically caused by population growth and public investment, not any action taken by owners. Economic theory suggests that taxing this income is actually preferable to taxing employment income,37 yet it is currently taxed at two thirds the rate of employment income (and one half the rate for individuals with under $250,000 in capital gains).

Preferential taxation for REITs can also have a distorting effect, especially when investments are in tax-sheltered accounts. This incentivizes investors to put their money in REITs, financialized firms that often use their capital to purchase existing rental housing, rather than in other, more productive forms of investment.

Recommendations

Solving the current housing affordability crisis will require radical changes to the way we provide housing in this country. Publicly- or cooperatively-owned and operated housing is urgently needed so that housing can be provided without its owners trying to maximize extraction of rents. At the same time, the tax system should not incentivize this behaviour. Martine August’s summary report to the Office of the Federal Housing Advocate makes a wide range of recommendations that could help address this problem. These include implementing broader rent control policies, including vacancy control, and limiting ownership of rental housing by financial firms. We further recommend significant construction of non-market housing coupled with an end to tax policy that encourages financialization:

- Build 1 million non-market homes over the next decade.

- End preferential tax treatment for REITs. There is no reason that the tax system should offer tax breaks for people to profit off of renters. After promising to review the measure, the federal government announced in early 2024 that it would not be moving forward. The Parliamentary Budget Office has estimated that closing this loophole would raise over $50 million per year,38 enough to build at least 250 affordable units every year.

- Full inclusion of inflation-adjusted capital gains in taxable income, especially for the FIRE sector. Large corporations should not get tax breaks for owning land that appreciates in value without productive investment.

- Extend the underused housing tax to apply to properties owned by Canadians. The underused housing tax discourages housing speculation by imposing a 1% tax on properties that are left vacant, but currently only applies to housing owned by foreign nationals. Vancouver and BC have implemented similar taxes that apply to all residents and have experienced significant reductions in vacant housing.

End notes:

¹ Martine August, 2020, The financialization of Canadian multi-family rental housing: From trailer to tower, Journal of Urban Affairs, 42:7, 975-997. DOI: 10.1080/07352166.2019.1705846

² Statistics Canada, 2024, Tables 33-10-0500-01 and 33-10-0499-01.

³ Ben Carlson, 2023, Buy & Hold is Dead, Long Live Buy & Hold, A Wealth of Common Sense.

⁴ This is not to say that GDP is an accurate measure of real economic value. Some purely financial transactions, such as interest payments, are included in GDP. Some real economic activity, like unpaid household labour, is not included in GDP.

⁵ Throughout this report, capital gains refer to book capital gains, that is, capital gains recorded on company financial statements. They may not exactly equal 2 times taxable capital gains reported by the CRA because corporate accounting methods can differ from those used by the CRA to calculate capital gains.

⁶ These figures are based on the Financial and Taxation Statistics for Enterprises. This source does not include enterprises in certain NAICS categories (526, 55, 8131, 81394, and 91) so it is a slight underestimate of the corporate sector as a whole.

⁷ We use this term to refer to NAICS category 523, “Securities, commodity contracts, and other financial investment and related activities”, which includes investment brokers and portfolio managers. Most of the capital gains in this industry are recorded by firms in the subcategory “Miscellaneous intermediation” which includes land speculators, oil royalty dealers, and venture capital firms.

⁸ The Globe and Mail, 2024, Real Estate. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

⁹ Investors in REITs are known as “unitholders”, which are akin to shareholders for corporations.

¹⁰ Eskandar Elmarzougui, April 3, 2023, Cost of removing the tax exemptions for Real Estate Investment Trusts, Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer.

¹¹ The proportion of distributions designated as capital gains was 62.2% and distributions were $234 million.

¹² Martine August, 2022, The financialization of housing in Canada, Office of the Federal Housing Advocate.

¹³ Martine August, 2022, The financialization of multi-family rental housing in Canada, Office of the Federal Housing Advocate.

¹⁴ Statistics Canada, 2023, Table: 46-10-0070-01, Investment status of residential properties.

¹⁵ Statistics Canada, 2022, To buy or to rent: The housing market continues to be reshaped by several factors as Canadians search for an affordable place to call home.

¹⁶ Canadian Apartment Properties REIT, 2024, Focused on Quality: 2023 Annual Report.

¹⁷ A capitalization rate (or “cap rate”) is the proportion of an asset’s value that it returns each year. If a $1 million property produces $50,000 in net income each year, then it has a cap rate of 5%.

¹⁸ Boardwalk REIT’s annual report says that measuring the value of the trust’s investment properties (that is, the living quarters of thousands of Canadians) requires “a forecasted stabilized [net operating income (NOI)] for each individual property be divided by a Cap Rate to determine a property’s fair value. NOI is calculated as a one-year income forecast based on rental income from current leases and key assumptions about rental income, vacancies and inflation rates, among other factors, less property operating costs”.

¹⁹ This refers to 12 month same property figures. See p. 44 of their 2023 annual report.

²⁰ Martine August and Julie Mah, 2024. Evictions, Spatial Inequality, and the Financialization of Rental Housing in Toronto. Working Paper. Presented at the BSH Spring Workshop, held in Toronto May 28-30, 2024.

²¹ Centurion Apartment REIT, 2024, 2023 Annual report.

²² Martine August, 2022, The financialization of housing in Canada, Office of the Federal Housing Advocate.

²³ CMHC, 2024, Rental Market Report.

²⁴ May Warren, December 2023, Toronto-based developer that vowed to buy up $1 billion in single-family homes plans to add 10,000 more houses to its portfolio.

²⁵ Jim Stanford, January 2024, Real Wages are Recovering… and That’s Good News! Centre for Future Work.

²⁶ Returns of capital essentially allow investors to treat income earned through other forms as deferred capital gains. Income distributed in this form is not taxable when distributed but reduces the cost base of the unit so that investors will trigger a larger capital gain when they sell their unit. This is beneficial for investors because it allows them to benefit from the low capital gains inclusion rate, and defer even those lower taxes.

²⁷ Five of these seven REITs, CAP, Killam, Boardwalk, InerRent and Minto have formed a policy advocacy organization called Canadian Rental Housing Providers for Affordable Housing. This organization has asked the government to increase transfers to tenants while in 2023 they increased average same property rent by 7%.

²⁸ Statistics Canada does not regularly publish decompositions of profits into each of these sub-sectors. For 2006, operating profits by sub-sector is available and the breakdown was as follows: lessors of non-residential real estate (43%), lessors of residential real estate (30%), real estate agents and brokers (21%), real estate property managers (5%), real estate appraisers (1%).

²⁹ Silas Xuereb, 2024, Profits rise as investment stalls in Canada’s affordability crisis, Canadians for Tax Fairness.

³⁰ Boardwalk REIT, 2024, Inspiring solutions, transforming communities: 2023 annual report.

³¹ Ibid.

³² Isabella M Weber and Evan Wasner, 2023, Sellers’ Inflation, Profits, and Conflict:

Why Can Large Firms Hike Prices in an Emergency?, Political Economy Research Institute Working Paper 571.

³³ Isabella M Weber, Jesus Lara Jauregui, Lucas Teixeira, Luiza Nassif Pires, 2024, Inflation in times of overlapping emergencies: Systemically significant prices from an input–output perspective, Industrial and Corporate Change, Volume 33, Issue 2.

³⁴ Ryan Romard, 2024, Productivity and capital gains inclusion rates, Canadians for Tax Fairness.

³⁵ Henry George, 1879, Progress and Poverty.

³⁶ Stuart Adam et al., 2011, The Taxation of Land and Poverty, In Tax By Design.

³⁷ Gregor Schwerhoff, Ottmar Edenhofer, and Marc Fleurbaey. "Taxation of economic rents." Journal of Economic Surveys 34.2 (2020): 398-423.

³⁸ Eskandar Elmarzougui, 2023, Cost of removing the tax exemptions for Real Estate Investment Trusts, Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer.