Budget 2024 took a significant step towards tax fairness by increasing the capital gains inclusion rate on Canada’s richest individuals and corporations. Tellingly, a measure designed to tax the rich to fund crucial public investments has caused a wave of outrage amongst a very vocal minority.

But while the 0.13 percent of tax filers and 12 percent of corporations impacted by the change are predictably throwing a tantrum, the wave of analysts and pundits fearmongering on their behalf shouldn’t be taken too seriously.

For decades, there’s been a yawning tax gap between wage earners and wealthy investors. When it’s tax time, 100 percent of workers’ wages are included in their taxable income, whereas only 50 percent of capital gains through sales of investments are included in the calculation of income for those who derive their earnings through investments.

The 2024 federal budget proposes a modest change to this arrangement, increasing the taxable portion of annual capital gains above $250,000 to 66 percent for individuals. Corporations will face the same increased inclusion rate, albeit without the $250,000 exemption.

The change will be welcomed by many Canadians as it creates a fairer tax system and encourages public investment, but critics—many of whom are right-wing economists and pundits—have taken their outrage to the media and received outsized attention for their efforts.

These advocates for the wealthiest Canadians have argued that increasing the capital gains inclusion rate from half to two-thirds will lead to ‘brain drain,’ harm Canada’s productivity, and lead to a mass capital exodus. Yet, the proposed measure is estimated to have a very narrow impact on only 40,000 of the wealthiest Canadians (0.13 percent of the population). These individuals have an average annual income of $1.4 million.

How about the facts?

A marginal increase in the taxation of capital gains does not have a negative impact on investment and claims of lower productivity are unfounded.

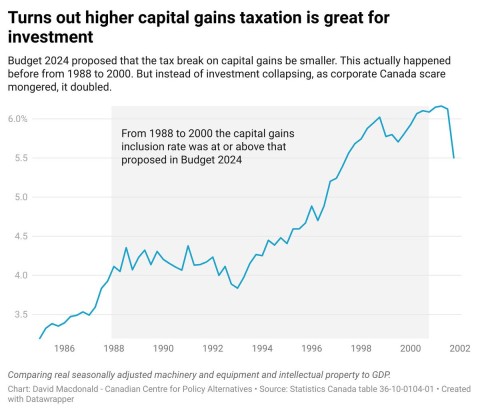

This also isn’t the first time that the capital gains tax break has been reduced. As revealed by David MacDonald, Senior Economist at the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, from 1988 to 2000 the capital gains tax rate was at or above the rate proposed in Budget 2024. During that period, corporate investment in research and development and machinery increased from 3.5 percent to six percent of GDP.

According to MacDonald, corporate investments follow the business cycle, not marginal tax changes.

Progressive economists are not the only ones throwing cold water on the claim that the capital gains tax increase will harm the middle class and drive out investment.

In an annual “fireside debrief” of the federal budget, a senior partner at Ernst & Young, one of the big four accounting companies, joked that he had been expecting an increase to the capital gains inclusion rate for a number of years now.

Firms like EY aren’t overly concerned about the tax measures in the budget because they know that even with this modest change to the capital gains inclusion rate, there are still a number of ways that ulta-rich Canadians and corporations can continue to enjoy low taxation.

Some example include capital loss deductions; the lifetime capital gains exemption; the proposed employee ownership trust exemption; and the proposed Canadian Entrepreneurs Incentive, which would reduce the capital gains inclusion rate to one-third on a lifetime maximum of $2 million in eligible capital gains.

Wealthy Canadians also enjoy historically low corporate income tax rates, a relatively low top marginal tax bracket, and the lowest marginal effective tax rate in the G7. Combined, these tax breaks continue to fuel increased wealth and income inequality across Canada.

The increase to the capital gains inclusion rate is a welcome policy measure to claw back some of the wealth accumulated by the richest Canadians. But we can do more to create an equitable future for everyone. Wealth inequality is at critical levels not seen in a century. The top decile of wealth holders have over 60 times the wealth of those in the bottom half.

Partially closing the capital gains loophole is a step in the right direction, but Canada can and should go further.

US President Joe Biden recently went strong on tax fairness, announcing a number of tax proposals for the 2025 budget to help ordinary workers and rebalance America’s economy.

Perhaps it’s time to implement some of what EY’s National Leader of Tax Policy, Fred O’Riordan, called “ugly tax measures”—a higher marginal tax bracket for the richest, an excess profits tax, and a wealth tax.

After all, what may be ugly to the richest and most powerful is necessary to sustain the rest of us.

This piece originally appeared in Canadian Dimension.