Résumé

In 2023, corporations raked in $644 billion in pre-tax profits, 54% higher than 2019, the last pre-pandemic year, and over double the average profit levels of the pre-pandemic decade. If an increase in profits was entirely explained by inflation, profit margins, that is, the total profits of firms divided by their total revenue, would stay the same. However, pre-tax profit margins increased significantly during the pandemic. In 2021 and 2022, the average pre-tax profit margin was over 12%, and it remained at 10.7% in 2023. Between 2010 and 2019, pre-tax profit margins averaged only 8.1%.

It is commonly believed that higher corporate profits lead to higher corporate investment. Yet, despite their profits doubling after the pandemic, non-financial corporations did not increase their investment in the Canadian economy. Average non-financial corporate investment was $205.9 billion per year from 2010-2019 and $205.1 billion from 2021 to 2023. Instead, firms have used higher profits to repurchase their own shares and pay dividends, processes that inflate returns for shareholders without contributing to higher wages or productive investment that could boost future growth. In 2023, dividends and share repurchases were 68.2% of non-financial corporations’ net profits.

Profit margins remained above their pre-pandemic average in 18 of the 21 largest non-financial industries in 2023. Oil and gas extraction experienced the largest increase in profit margins - after averaging a -5.4% profit margin before the pandemic, the sector had a 17.6% profit margin in 2023. Grocery stores are typically a low margin industry, yet their profit margin doubled from 2.0% pre-pandemic to 4.1% in 2023.

Conventional economic theory, which asserts that profits reflect the marginal productivity of capital, cannot explain this economy-wide increase in profit margins. Instead, increasing profit margins reflect an increase in firms’ price-setting power due to reduced competition and policies less favourable to labour organizations.

Increased corporate profit margins contributed to the high levels of inflation experienced since 2021 and led to increasing income inequality in 2021. New policies are needed to bring profit margins back down, curb the power of the largest corporations, and ensure a fairer distribution of Canada’s resources. An increased corporate income tax rate, a minimum tax on book profits, and prevention of further corporate consolidation would contribute to these ends and raise revenue to fund much-needed public investment.

Rapport

Corporate profits during the pandemic

Across all sectors, corporate profits reached record levels during the COVID-19 pandemic, peaking in 2022 (see Figure 1). In 2022, corporations raked in $685 billion in pre-tax profits, 64% higher than 2019, the last pre-pandemic year. While 2023’s corporate profits sit slightly lower at $644B, that is still over double the average profit levels of the pre-pandemic decade.

Figure 1. Total pre-tax corporate profits by year, 2010-2023. Source: Statistics Canada Table: 33-10-0224-01

Because inflation increases the price of goods, it could cause total profits to increase without changing the distribution of income in the economy. However, while some of the rise visible in Figure 1 can be attributed to inflation, most cannot. If an increase in profits was entirely explained by inflation, profit margins, that is, the total profits of firms divided by their total revenue, would stay the same. Examining profit margins can show whether increases in profits are attributed to firms facing increasing costs or to firms choosing to increase prices.

Figure 2 shows that pre-tax profit margins increased significantly during the pandemic. In 2021 and 2022, the average pre-tax profit margin was over 12%. Between 2010 and 2019, pre-tax profit margins had never exceeded 10% and averaged 8.1%. If corporations had increased prices in line with increases in their input costs (e.g., raw materials, wages), profit margins would have stayed constant. Instead, it is clear that corporations chose to increase prices far more than their input costs increased. The Competition Bureau showed the same for the grocery industry in particular.

Figure 2. Pre-tax profit margins by year, 2010-2023. Source: Statistics Canada Table: 33-10-0224-01

Has this changed in 2023 as the pandemic receded and inflation began to fall? While corporate profits came down from their peak in 2023, they remained far higher than their pre-pandemic levels. In 2023, total pre-tax corporate profits were $644 billion, and the profit margin was 10.7%, still well above pre-pandemic levels.

Elevated corporate profits have not led to increased investment

A common argument is that corporate profits are good for the economy because companies reinvest them, increasing productivity and driving future growth. However, this is not what happened during the COVID-19 pandemic. As shown in Figure 3, corporate capital expenditures1 of non-financial corporations have remained roughly constant since 2010. There are small annual fluctuations but there was certainly no significant rise in 2021- 2023 when corporate profits reached record levels. In the pre-pandemic decade, non- financial corporate investment averaged $205.9 billion per year. From 2021 through 2023, non-financial corporate investment averaged $205.1 billion per year.

In a recent report, Statistics Canada analysed firm-level data and found there was no relation between profits and investment at the firm level from 2006 through 2019. Instead, Statistics Canada attributed the slowdown in investment to a failure to properly measure intangible assets and a decline in competition.2 Of course, we need more investment, but allowing corporations to keep more profits does not lead to increased investment.

Figure 3. Non-financial corporate pre-tax profits and capital expenditures, 2010- 2023. Source: Statistics Canada Table: 33-10-0225-01

Instead, firms have used high profits to repurchase their own shares, a process commonly known as stock buybacks, which inflates returns for shareholders without contributing to higher wages or productive investment that could boost future growth. Figure 4 shows net share issuances from 2015 to 2023 - that is, the value of new share issuances less the value of share repurchases. Negative values indicate that corporations repurchased more shares than they issued in new shares.

In 2022 and 2023, while corporations were collecting record profits, corporations repurchased more shares than they issued. Corporations repurchased $86.4 billion worth of shares in 2021, $128.7 billion in 2022 and $87.3 billion in 2023. From 2015 through 2019, corporations only repurchased, on average, $60.7 billion of shares each year. It should be noted that part of the increase in share repurchases in 2022 and 2023 may have been in anticipation of the introduction of the 2% tax on share repurchases, announced in the 2022 Fall Economic Statement, which came into effect January 1, 2024. It remains to be seen whether this low tax rate will be sufficient to discourage companies from using share repurchases in the future.

Firms also use profits to pay dividends to shareholders. In 2023, non-financial corporations paid out $191.3 billion in dividends. This is nearly half (46.8%) of their net profits. Dividends and share repurchases, which directly increase the incomes and wealth of corporate owners, account for over two-thirds (68.2%) of non-financial firms’ net profits in 2023.3

Figure 4. Net share issuances (share issuances minus share repurchases), 2015-2023. Source: Statistics Canada Table: 36-10-0621-01

Which sectors have maintained elevated profits?

Previous work has shown which sectors experienced the largest increases in profits during the pandemic - banking, oil and gas, and groceries were some of the largest. In this section, we examine which sectors maintained these high profits in 2023.

Profit margins remain well above pre-pandemic levels for non-financial companies, although profit margins have returned to pre-pandemic levels for financial companies (see Figure 5). In 2023, however, the significant drop in the profit margin in the financial sector was more due to the growth of the sector (an increase in the volume of both revenue and expenses) than to a fall in total profits (total revenue increased from $563.4 billion in 2022 to $732.8 billion in 2023 while pre-tax profits only fell from $196.7 billion to $173.3 billion). According to recent work by the Centre for Future Work, the continued growth of the financial sector in 2023 was primarily driven by persistent high interest rates.

Figure 5. Profit rates in the financial and non-financial sectors, 2010-2023. Sources: Statistics Canada Table: 33-10-0225-01 and Table: 33-10-022701

Profit margins for 29 of 39 non-financial industries were higher in 2023 than their pre- pandemic average. Figure 6 displays average profit margins in the decade before the pandemic alongside profit margins in 2023 for 21 of the largest industries in Canada. All but three had higher profit margins in 2023 than pre-pandemic. Real estate stands out as the sector with the highest profit margin (largely due to the nature of real estate as requiring significant capital assets but little operating expenses), although its profit margin was lower in 2023 than before the pandemic. Oil and gas extraction experienced the largest increase in profit margins - after averaging a -5.4% profit margin before the pandemic, the sector had a 17.6% profit margin in 2023. Grocery stores are typically a low margin industry, yet their profit margin doubled from 2.0% pre-pandemic to 4.1% in 2023. Profit margins also increased substantially in gas and coal manufacturing, and for automotive dealers.

Figure 6. Pre-pandemic and 2023 pre-tax profit margins by non-financial industry. Source: Statistics Canada Table: 33-10-0225-01. Note: Only sectors with at least $100 billion in revenue in 2023 are included.

Why are corporate profits still so high?

Conventional economic theory, which assumes perfectly competitive markets, suggests that profits4 are a direct measure of the productivity of capital - according to the theory, factors of production, including both capital and workers, are compensated according to the amount they contribute to the product. This would force us to conclude that, in nearly every major industry in Canada, capital has become much more efficient and productive since the COVID-19 crisis, a dubious claim at best.

From this perspective, higher profits can result from less competitive markets, labour organizations losing power, or government policies that provide corporations more favourable conditions. External inflationary pressures, such as the supply-chain disruptions that occurred during the COVID-19 crisis, can also provide corporations with cover to increase prices to achieve higher profits because consumers are already expecting price increases.5 Over time, firms’ price-setting power has increased,6 as corporate consolidation has advanced and government policies have become more favourable to corporations relative to labour organizations. In one recent concrete example, the Federal Trade Commission found that American oil producers colluded with OPEC during the pandemic to inflate oil prices.7

Alternatively, profit levels can be viewed as a reflection of the power of corporations. Corporations always have a degree of price-setting power and can increase profits through increasing their prices. The degree of price-setting power any firm has depends on many different factors, including the competitiveness of the market, the power of labour organizations, and government policies.

This approach provides a much more convincing explanation for the increase in profit margins observed during the COVID-19 pandemic and its post-pandemic persistence - corporations, with a degree of pre-existing price-setting power, were able to increase prices more than their costs increased and benefited from significant government subsidies. For profit levels to come down again, governments or labour organizations must force them to. Else, corporations will continue to use their price-setting power to maintain high profit margins, at the expense of the rest of us.

High corporate profits have contributed to increasing inflation and inequality

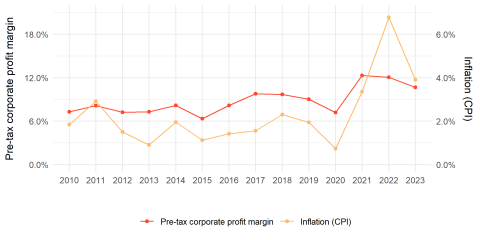

How do these continued elevated corporate profits affect average Canadians? Well, for one, they can contribute significantly to inflation. As described above, firms’ price- setting power allows them to increase prices to achieve higher profits, and this power is increased during periods of inflationary pressure, like the beginning of the COVID- 19 crisis. So, although high profits were by no means the only cause of the high levels of inflation observed since 2021, they certainly contributed to the rising price level. MacDonald showed that between Q3 2020 and Q3 2022, 41% of dollars paid for higher prices went to corporate profits, while only 34% went to higher wages. Figure 7 shows inflation according to the consumer price index and pre-tax corporate profit margins from 2010 to 2023. There is clearly a correlation between the two measures. The three highest years of profit margins (2021-2023) coincide with the three highest years of inflation.

Figure 7. Pre-tax profit margins and Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation, 2010-2023. Sources: Statistics Canada Table: 33-10-0224-01 and Table: 18-10-0005-01

What do high corporate profits and high inflation mean for the income distribution in Canada? Higher incomes for the wealthy and lower incomes for lower and middle classes. Corporate profits are sometimes retained in corporations, sometimes used for stock buybacks, and sometimes used to pay dividends to shareholders. Each of these uses benefit the owners of corporations, who are predominantly among the richest 1% of Canadians. In 2021 (the last year with available data), the first year with a significant spike in corporate profits, the average market income of the top 1% of income earners increased by 13%, from $508,600 to $576,100. From 2019 to 2021, the average market income of the top 1% increased by 13% while the average market income of the bottom 50% was unchanged.

Figure 8. Market income shares for the top 1% and bottom 50% of income earners, 2017- 2021. Source: Statistics Canada Table: 11-10-0055-01

When capital gains are included, the picture is even more stark. Including capital gains, market incomes for the top 1% increased by 29% from 2019 to 2021 while they increased by 2% for the bottom 50%. Figure 8 shows the impact this had on the income shares of the top 1% and bottom 50%. Data is not yet available for 2022 and 2023 but given the continued elevated corporate profits, these trends likely continued during these years.

Conclusion

In 2023, corporate profit margins continued to far exceed their pre-pandemic levels. This is harmful to most Canadians because high corporate profit margins are associated with higher levels of inflation and higher income inequality. Contrary to the idea that profits allow corporations to invest more, the evidence shows that increased profits during the pandemic had no effect on investment. Instead, profits were used to repurchase shares and pay dividends to shareholders. To bring profit levels back down, we need government intervention and public pressure on corporations not to increase prices. Here are some steps that could be taken:

- Raise the corporate income tax rate to 20%. Before the Harper government, the federal corporate income tax rate was 22%. The CIT rate fell to 15% in 2012 and has not led to an increase in investment in Canada.

- Implement a minimum book profits tax of 15%. A minimum book profits tax ensures that corporations are not able to use tax deductions and loopholes to reduce their tax payable to 0. A version of this tax was implemented in the USA on January 1, 2023.8

- Use the newly strengthened Competition Act to prevent market consolidation that can lead to excess profits. Canada’s competition bureau has been notoriously permissive towards mergers, which has contributed to the enormous price-setting power Canadian corporations have today.

- Use the $18 billion of annual revenue raised through increased corporate taxation9 to fund public investments in housing, education, and research and development. Award-winning economist Mariana Mazzucato has shown that public investment is the strongest driver of private investment in renewable energy projects,10 leads to the development of most innovative pharmaceuticals,11 and drives economic growth.12

ABOUT CANADIANS FOR TAX FAIRNESS

Canadians for Tax Fairness is a non- profit, non-partisan organization that advocates for fair and progressive tax policies, aimed at building a strong and sustainable economy, reducing inequalities, and funding quality public services.

ABOUT SILAS XUEREB

Silas Xuereb is a researcher with years of experience in academia and working with non-profit organizations. He's passionate about conducting rigorous research to understand social and economic inequalities in support of actors working to alleviate them. He holds Master’s in Economics from UBC and the Paris School of Economics and is currently a PhD student at UMass Amherst.

END NOTES:

1 Corporate capital expenditures include spending on new buildings, machinery and equipment, used buildings, used machinery, land, capitalized leases, and depletable assets.

2 Wulong Gu, 2024, “Investment Slowdown in Canada After the Mid-2000s: The Role of Competition and Intangibles”, Statistics Canada.3 Author’s calculation based on Table: 33-10-0225-01 and Table: 36-10-0621-01

4 Neoclassical economic theory uses the term profits differently than I use it here. My use of the term profits here is similar to neoclassical theory’s return to capital.

5 Isabella M Weber, Evan Wasner, 2023, “Sellers’ Inflation, Profits and Conflict: Why Can Large Firms Hike Prices in an Emergency?” Review of Keynesian Economics.

6 Jan De Loecker, Jan Eeckhout, Gabriel Unger, 2020, “The Rise of Market Power and the Macroeconomic Implications”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics.

7 Matt Stoller, 2024, “An Oil Price-Fixing Conspiracy Caused 27% of All Inflation Increases in 2021”, BIG.

8 Tax Policy Center, 2024, “What is the Book Minimum Tax on corporations?”, Urban Institute and Brookings Institution.

9 AFB Working Group, 2023, “AFB 2024: Taxation”, Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

10 Matteo Deleidi, Mariana Mazzucato, & Gregor Semieniuk, 2020, “Neither crowding in nor out: Public direct investment mobilising private investment into renewable electricity projects,” Energy Policy.

11 Mariana Mazzucato, 2024, “Rethinking Innovation in Drugs: A Pathway to Health for All,” Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics.

12 Giovanna Ciaffi, Matteo Deleidi, & Mariana Mazzucato, 2024, “Measuring the macroeconomic responses to public investment in innovation: evidence from OECD countries”, Industrial and Corporate Change.